Welcome to the final installment of the Syntax Goals for Speech Therapy series, where I break down how to write the best speech therapy goals for syntax that focus on high-priority skills to build listening and reading comprehension.

In this article series, I’ve broken down four challenging sentence types and how to target them (described by Richard Zipoli’s 2017 article in Intervention in School and Clinic).

We know that our students have disorganized language, but aren’t always sure where to start. It’s easy to feel kind of lost when writing speech therapy goals for syntax. Especially when we know something isn’t right, but we can’t quite put our finger on what it is.

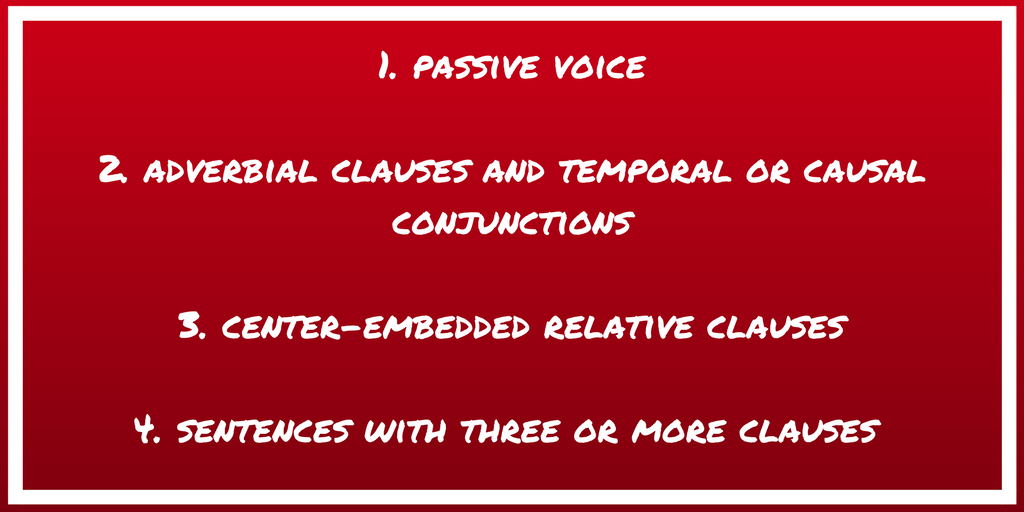

I’ve set out to solve that problem with this series. Here’s what we’ve covered so far in the first four articles:

In the first article, I talked about why syntax is so important, and what “base goal” we can use as a framework for writing all of our IEP goals for syntax.

In the second article, I talked about how to write speech therapy goals for syntax when your students struggle with passive voice, and how to use pictorial support to build this skill.

In the third article, I shared what to do when your students are struggling to use sentences with adverbial clauses and temporal/causal conjunctions. I also covered what that even is (I have to look this stuff up too) and why it’s important for us to know.

Here are those four sentences types SLPs can consider when we write speech therapy goals for syntax:

Now, let’s talk about the fourth one:

Sentences with three or more clauses.

We already know that our students tend to stick to simple sentences; which contain just one clause.

But sometimes we really need to challenge students when we come up with speech therapy goals for syntax, because it’s even harder for them to understand and use sentences containing three or more clauses.

The fact is, they often need to be able to both understand and use sophisticated sentences if they’re going to succeed in school.

Yet students with language disorders tend to have poor working memory, and just can’t remember all of the details when there are multiple pieces of information (Erickson, 2017, Owens, 2016).

The best thing we can do is learn to break it down for them so they can process each piece of information.

Let’s see if we can do that with a couple examples of sentences that have three or more clauses:

“We went home before we finished our picnic because it started raining.”

Can you count the clauses?

Independent clause: “We went home”

Dependent clause with temporal conjunction: “before we finished our picnic”

Dependent clause with causal conjunction: “because it started raining”

Here we have a total of three clauses, so it’s possible that the student may not remember the agent and receiver of the action for each one.

They also have to understand the meaning behind the temporal conjunction (before) that tells us when we went home and the causal conjunction (because) that helps explain why we went home when we did.

This is a lot to process at once.

Here’s another example:

“Mom called me yesterday before she made dinner because she wanted me to get home on time.”

Let’s count the clauses again (and see if we can find some of those other syntactic structures I’ve talked about in the last few articles:

Independent adverbial clause: “Mom called me yesterday.”

Dependent clause with temporal conjunction: “before she made dinner”

Dependent clause with causal conjunction: “because she wanted me to get home on time”

Our students can have the same issues here as with the first example. There are multiple agents and receivers within this sentence.

And will our students understand that mom had to call me FIRST, and THEN she made dinner?

Will they get that the call from mom caused me to get home on time?

Will they understand that all of these events happened YESTERDAY, and not TODAY?

Just for fun, let’s do one more:

“After eating lunch, I cleaned the dishes while our guests who were visiting ate dessert.”

The clauses are:

Independent clause: “I cleaned the dishes”

Dependent clause with temporal conjunction: “after eating lunch”

Dependent clause with temporal conjunction: “While our guests ate dessert”

Center-embedded relative clause: “who were visiting”

With four clauses total, and one of them being embedded, this will be an earful for our students.

Now that we’ve done that exercise, let’s talk about writing speech therapy goals for syntax.

If you want your students to improve their ability to starting using and understanding more sophisticated sentences, I’d recommend focusing your goal on complex sentences and conjunction use.

In this previous article, I talked about how we could include either complex sentences, conjunctions, or BOTH in our goal statement.

The reason I say you can do either when writing speech therapy goals for syntax is because we need to use conjunctions when we say complex sentences, so if you have a goal for complex sentences its assumed that you’re working on conjunctions too.

If we were to write a goal that address conjunctions, this could cover complex sentences, and it could also cover compound sentences or simple sentences with compound subjects or verbs. It’s not as specific, but you’re still covered under that goal.

That all being said, if you’re main focus in writing the goal is to get your students to say more sophisticated sentences (like sentences with three or more clauses), I’d go with something like this:

“Students will write/say complex sentences on 4/5 trials.”

I’d recommend mentioned complex sentences in this case because this way you know the main focus is to use multiple clauses, and simply getting your students to use conjunctions alone may not require this (for example, when you use “and” in a compound subject).

Now, let’s say you’ve got a student who might be able to push this goal a bit further and start working on sentences with more than two clauses? You could be covered with the goal I’ve stated above, but to make it more specific you could say:

“Student will say/write complex sentences with 3 or more clauses on 4/5 trials.”

For our comprehension goal, what I’d be likely to write would be this:

“Student will answer questions about complex sentences on 4/5 trials.”

Or even something broader like:

“Student will answer “wh” questions about sentences or short paragraphs (3-4 sentences) on 4/5 trials.”

If I wrote this broader goal, I’d really make sure that I used a variety of sentence types to ensure we were hitting everything the student needed.

Finally, if you absolutely felt that you needed a comprehension goal for sentences with three or more clauses, you could say:

“Student will answer “wh” questions about sentencse with 3 or more clauses on 4/5 trials.”

The treatment techniques for sentences with multiple clauses that Zipoli (2017) recommends are sentence decomposition and sentence combining.

When you use sentence combining, you are giving students more than one sentence and asking them to combine them in to one sentence.

Sentence decomposition is the opposite; you are taking one complex sentence and deconstructing it.

Because I’ve talked about sentenced decomposition in the article about center-embedded relative clauses, I’ll expand on that.

This way, you’ll be able to target these two sentence types together if you want.

I’ve essentially done sentence decomposition with you in the examples above with the sentence examples. All you would need to do now is do that same exercise with your students, and then possibly have your students try to put those sentences back together again.

With that, this brings us to the end of the series. I hope you’re leaving with a solid IEP goal bank that will show you how to write effective speech therapy goals for syntax, along with some solid strategies for getting your students to meet them.

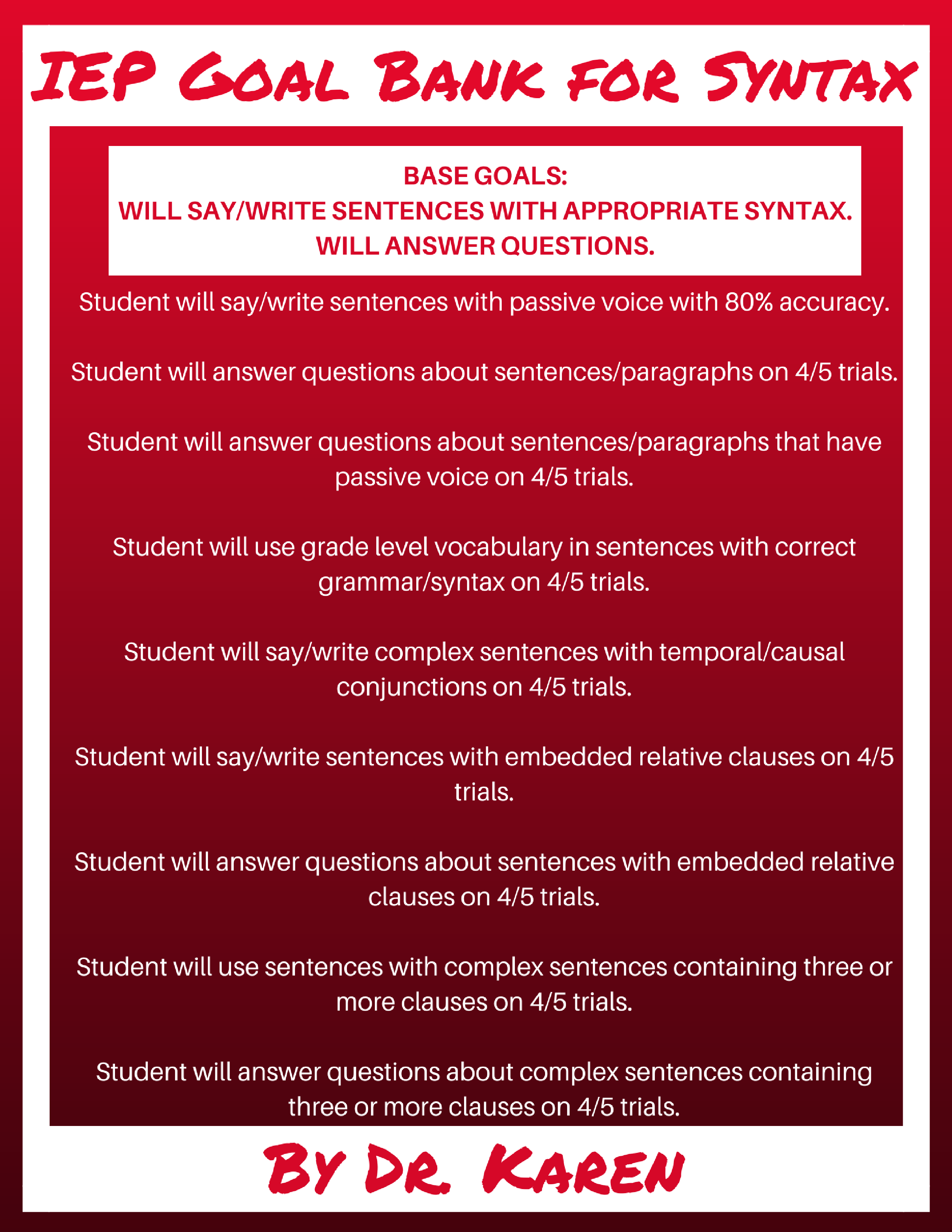

Here’s that final IEP goal bank (I’ve picked the simplest versions of the goals I’ve discussed in this article):

This brings this epic guide to an end…but there will be more articles just like this to come on my blog.

Inside you’ll learn exactly how to focus your language therapy. Including:

References